Male Fish In North Carolina Rivers Found To Have Female Parts

Some black bass and sunfish in North Carolina rivers have eggs in their testes; researchers suspect chemical exposure as culprit and are concerned for populations

By Brian Bienkowski, Environmental Health News

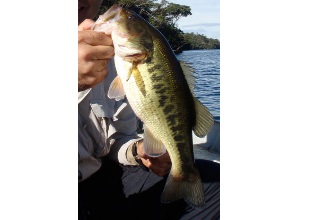

Male black bass and some sunfish in North Carolina rivers and streams are developing eggs in their testes, which can cause reproductive problems and potentially threaten populations, according to unpublished research.

The research adds to growing evidence that exposure to estrogen compounds is feminizing male fish across the U.S. and suggests that North Carolina fish might be particularly at risk.

“It’s a very interesting study and certainly adds to our understanding of what’s potentially going on in our rivers and with the intersex fish,” said Vicki Blazer, a U.S. Geological Survey fish biologist who was not involved in the study.

North Carolina State University researchers tested 20 streams and rivers throughout North Carolina during the 2012 spawning season for contaminants known to disrupt endocrine systems, such as industrial chemicals and pesticides. They also tested black bass—largemouth and smallmouth bass—and sunfish in the rivers for “intersex” characteristics, looking for eggs in the testes of males.

More than 60 percent of the 81 black bass tested intersex, while 10 percent of the 185 sunfish were intersex. They detected 43 percent of the 135 contaminants they were looking for throughout the state. Crystal Lee Pow, a Ph.D. student at North Carolina State University who helped lead the work, said they are still analyzing differences between waterways so aren’t yet disclosing the impacted rivers.

More than 60 percent of the 81 black bass tested intersex, while 10 percent of the 185 sunfish were intersex. They detected 43 percent of the 135 contaminants they were looking for throughout the state. Crystal Lee Pow, a Ph.D. student at North Carolina State University who helped lead the work, said they are still analyzing differences between waterways so aren’t yet disclosing the impacted rivers.

The results are worrisome. In past studies, male fish with eggs have had reduced fertility and sperm production. In addition, male fish are critical for the survival of developing black bass and sunfish.

“Males guard the nest, create spawning nests for young, and guard fertilized eggs,” Lee Pow said. “ Males are crucial for hatching success, and their male behavior could be altered by exposure to contaminants and the presence of the intersex condition.”

The research was in part spurred by a U.S. Geological Survey study in 2009 that showed intersex male fish in nine U.S. river basins and found that the Pee Dee River basin—which spans North Carolina and South Carolina—had the highest rate of intersex fish (80 percent).

The suspected culprits of the sex changes are endocrine disrupting compounds. This includes hormones, industrial chemicals and pesticides that are or mimic estrogen hormones. These compounds enter rivers and streams via permitted effluents, stormwater and agricultural runoff, and wastewater treatment plants, where excreted birth control and natural estrogens pass through relatively un-altered.

“There are also a lot of concentrated animal feeding operations in North Carolina,” Lee Pow said, adding that previous research at North Carolina State found that waste from pigs, which is held in lagoons, can run off into streams after it is applied to land. “The [pig] waste is chock-full of estrogens,” she said.

It’s unclear why the black bass had such a higher intersex rate, but it’s an important finding that shows not all species are impacted the same, said Dana Kolpin, a U.S. Geological Survey research hydrologist.

Blazer, who has been investigating intersex fish in the Potomac River basin and Chesapeake Bay drainage area, said Lee Pow’s findings are similar to hers—bass seem more prone to intersex characteristics.

“We’ve compared bass to white suckers, brown bullhead, and we rarely see intersex in the suckers and bullhead, even at the same sites where we see bass that are intersex,” Blazer said.

Researchers don’t know why the bass are more susceptible, however, it is probably either the timing and location of where they spawn, or something about their physiology that is more sensitive, Blazer said.

Donald Tillitt, a U.S. Geological Survey toxicologist, said he and colleagues dosed adult largemouth bass with a synthetic estrogen found in birth control pills with levels commonly found in the environment and were able to induce intersex fish.

“The dominant idea has been that intersex is instigated in early life exposures as the gonads are developing,” Tillitt said about the unpublished research. “But this suggests they’re still susceptible as adults.”

The presence of intersex black bass in North Carolina was linked to chemicals that are hydrophobic, meaning those that prefer separating from water such as the common contaminant polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs).

But Blazer cautioned that it is “important for people to understand that what could be inducing intersex at one site might be different than at another site.”

The concern with an impacted reproductive system is the overall fish population and ability to properly reproduce. Blazer said bass are a long-living fish and produce a lot of sperm, so it would take a few years for population impacts to take place.

Susan Massengale, a spokesperson for the North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources, said in an emailed response that the new study was “useful for understanding what may potentially affect aquatic life,” adding that it would be interesting to know the rivers tested and whether the tested fish had reduced ability to reproduce.

She said “this is one part of a picture that will emerge over time” as research fills in the blanks on the levels of these compounds that impact the fish and how to stop or treat the compounds before they affect species.

Kolpin said, with a growing body of evidence of endocrine disrupting compounds in U.S. waterways impacting fish, there may soon be action in trying to curb the problem.

“The next five years we should gain even more knowledge and eventually I think there will be something done to prevent contaminants getting into these waterways in the first place,” he said. “It’s better to prevent them than trying to treat water after the fact.”

Source: Environmental Health Sciences